the korean war Memorial

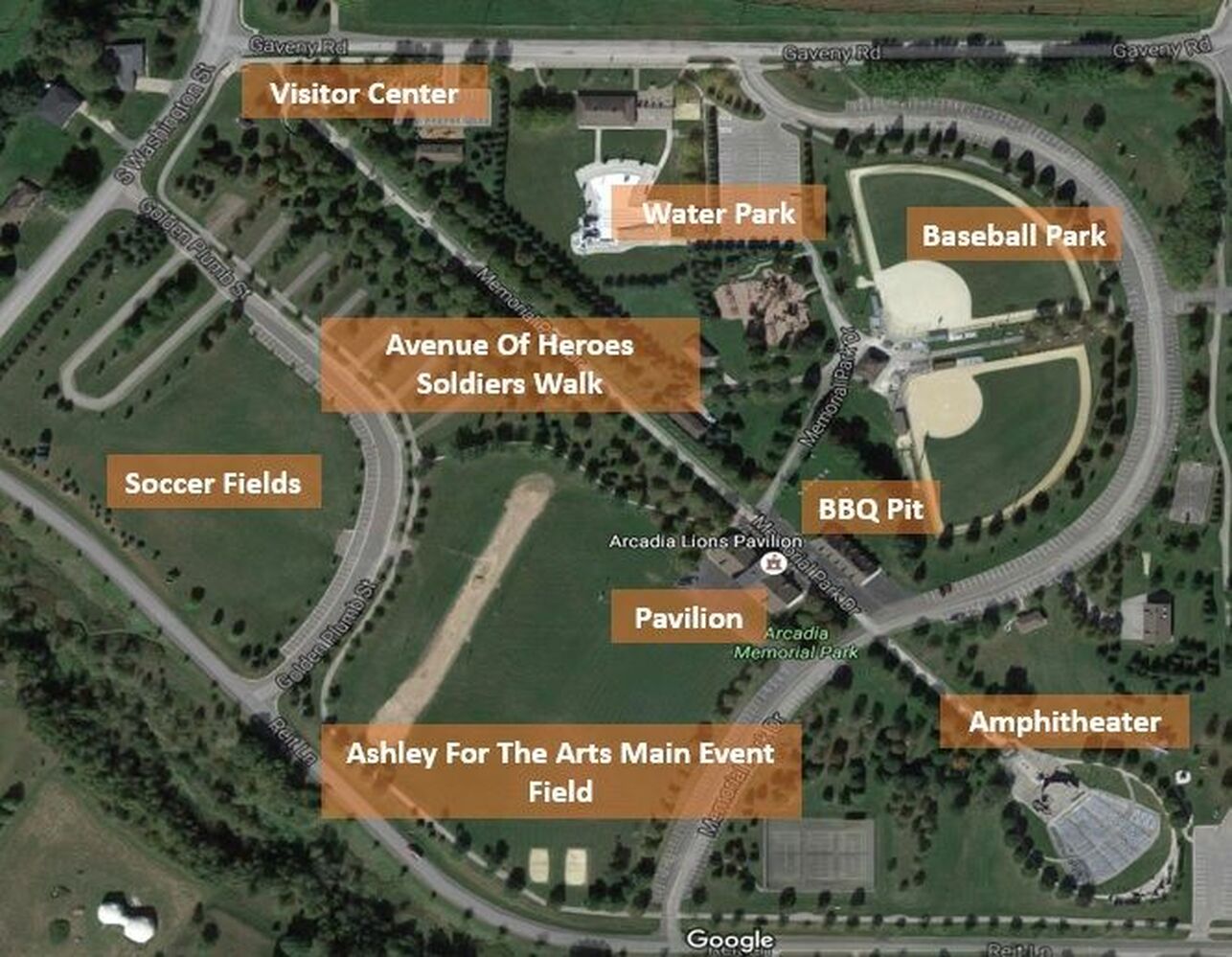

The Korean War, 1950–1953A memorial to the Korean war will be on the left side as you continue down Soldier's Walk. The memorial depicts 3 soldiers, an American soldier with their bayonet ready, another American soldier throwing a grenade and the third, representing a South Korean soldier carrying ammunition.

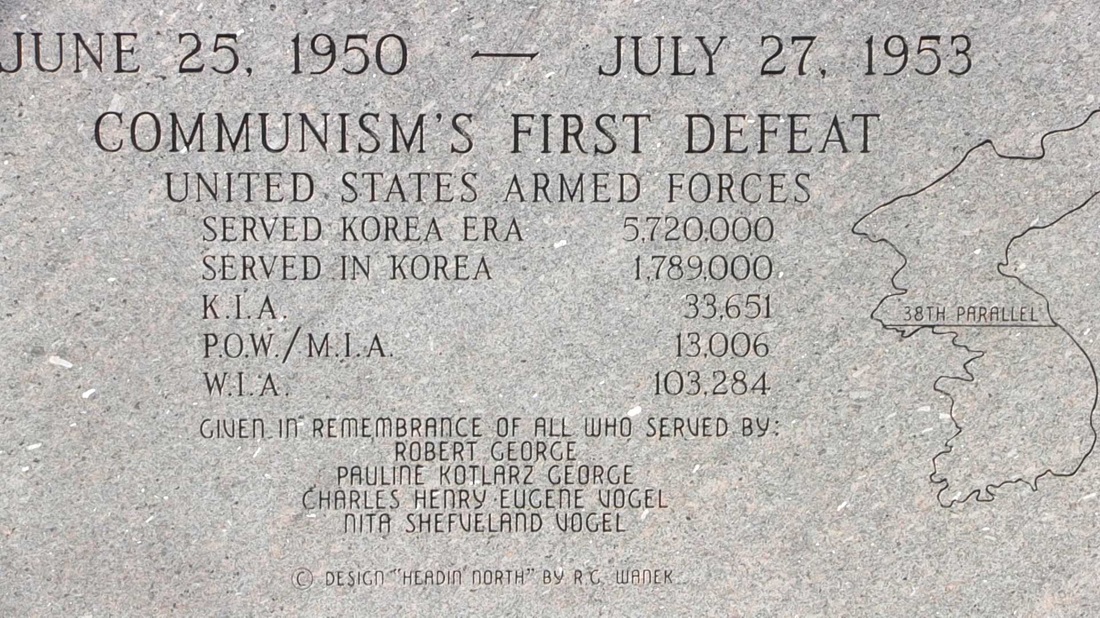

The memorial is a tribute to Communism's first defeat and shows where the action took place and the statistics of the conflict. It pays tribute to the 1,789,000 American's who served, including the 33,651 were killed in action, 103, 284 were wounded in action and 13,0006 were considered POW/MIA

The memorial was donated in remembrance by local Arcadia residents.

The memorial is a tribute to Communism's first defeat and shows where the action took place and the statistics of the conflict. It pays tribute to the 1,789,000 American's who served, including the 33,651 were killed in action, 103, 284 were wounded in action and 13,0006 were considered POW/MIA

The memorial was donated in remembrance by local Arcadia residents.

The Korean War began as a civil war between North and South Korea, but the conflict soon became international when, under U.S. leadership, the United Nations joined to support South Korea while the People’s Republic of China (PRC) entered to aid North Korea. The war left Korea divided and brought the Cold War to Asia.

The UN entry into the conflict led to a swift internationalization of what had been an internal struggle.

Though the United States dedicated the greatest number of troops to this conflict, soldiers from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and the United Kingdom also sent troops.

U.S. officials emphasized that this joint military action was imperative to prevent the conflict and communism from spreading outside Korea

The UN entry into the conflict led to a swift internationalization of what had been an internal struggle.

Though the United States dedicated the greatest number of troops to this conflict, soldiers from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and the United Kingdom also sent troops.

U.S. officials emphasized that this joint military action was imperative to prevent the conflict and communism from spreading outside Korea

Despite its long national history and unique cultural and linguistic identity, Korea suffered from frequent interference by its neighbors. China treated the Kingdom of Korea as a tributary state for centuries and fought Japan for influence on the Korean Peninsula in 1894–95. In 1904–05, the Russo-Japanese War was also fought largely on Korean territory. After the Japanese victory in that conflict, Japan consolidated its growing influence in Korea and in 1910, formally annexed it as a colony. Japan ruled Korea from 1910 until the end of World War II.

During World War II, the Allies discussed the future of Korea in the postwar period. The United States, Great Britain, and the Republic of China had met at Cairo in 1943, where they agreed that after its defeat, Japan would be stripped of all of its colonies, including Korea.

As the war drew to a close in August of 1945, two U.S. army colonels (one of whom, Dean Rusk, would later become Secretary of State) proposed that the Soviet Union take responsibility for accepting the surrender of Japanese troops in the part of the Korean peninsula north of the 38th parallel, whereas U.S. troops would receive the surrender south of that line.

This decision resulted in the division and separation of many villages along the 38th parallel and families with ties across that line.

The postwar planners had intended that the division between North and South Korea would be a temporary administrative solution.

After the war, the United Nations agreed to oversee elections in the North and South in 1947 in the hopes that it would lead to the reunification of Korea under a democratically elected government.

However, the Soviet Union blocked the elections in its section and instead, supported Kim Il Sung as leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

In the South, the United States supported SingMan Rhee as the elected leader of the newly founded Republic of Korea (ROK). Both Kim and Rhee were nationalists dedicated to the idea of reunification, although each ruled with a different ideological vision.

In 1949, under a UN agreement, both the Soviet Union and the United States withdrew their military forces from Korea, but both left large numbers of advisors on the peninsula.

The two sides were to continue negotiations over elections to reunify the country, and although the United States preferred that the resulting government not be communist, in 1949 it was still not prepared to commit militarily to preventing that outcome.

Both sides periodically instigated skirmishes across the 38th parallel, but the war formally began when the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, also known as the DPRK crossed the demarcation line and attacked the Republic of Korea the ROK on June 25, 1950.

Both Korean governments had been adamant about reunifying the peninsula, and the Soviet-supported DPRK saw an opportunity to do so with a swift strike.

The DPRK army quickly pushed into South Korea, and by September, it had engulfed almost the entire peninsula and had forced the ROK army into a small area around Pusan.

Upon hearing news of the attack, the United States immediately called for a meeting of the United Nations Security Council, which the Soviet Union was then boycotting over the issue of Chinese representation.

With the Soviets absent, the Security Council was able to pass a resolution condemning the actions of the DPRK and demanding that the Northern armies withdraw from the South.

The United States viewed the attack on the South as evidence that communism would actively challenge the free world and revised its security perimeter to include maintaining a non-communist South Korea. The UN sent forces composed of troops from 15 nations to the peninsula to stop the communist advance.

In September of 1950, UN forces led by U.S. General Douglas A. MacArthur managed to regain lost ground in South Korea and push north, forcing a reaction from the Chinese.

After landing at Incheon, near Seoul, MacArthur’s troops quickly moved to cut off the advancing DPRK army from its North Korean supply lines. By the end of the month, UN forces were approaching the 38th parallel, had liberated Seoul, and had restored the status quo that existed before the war.

The new question was whether to take this newfound success a step further and attempt to liberate the North from the rule of the DPRK.

The leadership of the U.S. and UN forces believed that an attempt to “rollback” the communist forces and unite the country under non-communist rule was well within the parameters of the mission. Chinese leaders had warned the international community that they would intervene in the conflict if UN forces pushed north of the 38th parallel, but MacArthur and other members of the UN command did not believe that either the People's Republic of China or the Soviet Union would attempt to halt UN forces.

With authorization from Washington, UN forces pressed north, and by October 1950 had nearly reached the Yalu River, which marks the border between China and North Korea.

Chinese officials viewed the UN forces approaching the Chinese border as a genuine threat to its security, and late in 1950 they sent Chinese forces into North Korea.

The U.S. and UN had also grossly underestimated the size, strength, and determination of the Chinese forces. As a result, MacArthur’s troops were quickly forced to retreat behind the 38th parallel.

In early 1951, the territory around Seoul and central Korea changed hands several times as the UN and Communist forces advanced and retreated.

MacArthur insisted on the extension of the conflict into China, and on April 11, 1951, he was removed from his command on the charge of insubordination and replaced by General Matthew Ridgeway.

By July 1951, the conflict had reached a stalemate, with the two sides fighting limited engagements, but with neither side in a position to force the other’s surrender.

Both the United States and China had, at this point, achieved the short-term goal of maintaining the demarcation line at the 38th parallel, while the North and South Koreans had failed in the larger goal of uniting the country under their preferred political systems.

Representatives of all the parties began to discuss peace.

On July 27, 1953, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, the Peoples republic of china and UN signed an armistice (the Republic of China abstained) agreeing to a new border near the 38th parallel as the demarcation line between North and South Korea. Both sides would maintain and patrol a demilitarized zone (DMZ) surrounding that boundary line.

The Korean War had long-lasting consequences for the entire region. Though it failed to unify the country, the United States achieved its larger goals, including preserving and promoting NATO interests and defending Japan.

The war also resulted in a divided Korea and complicated any possibility for accommodation between the United States and China.

The Korean War served to encourage the U.S. Cold War policies of containment and militarization, setting the stage for the further enlargement of the U.S. defense perimeter in Asia.

These Cold War policies would eventually lead the United States to regional actions that included its attempts at preventing the fall of Vietnam to communism.

During World War II, the Allies discussed the future of Korea in the postwar period. The United States, Great Britain, and the Republic of China had met at Cairo in 1943, where they agreed that after its defeat, Japan would be stripped of all of its colonies, including Korea.

As the war drew to a close in August of 1945, two U.S. army colonels (one of whom, Dean Rusk, would later become Secretary of State) proposed that the Soviet Union take responsibility for accepting the surrender of Japanese troops in the part of the Korean peninsula north of the 38th parallel, whereas U.S. troops would receive the surrender south of that line.

This decision resulted in the division and separation of many villages along the 38th parallel and families with ties across that line.

The postwar planners had intended that the division between North and South Korea would be a temporary administrative solution.

After the war, the United Nations agreed to oversee elections in the North and South in 1947 in the hopes that it would lead to the reunification of Korea under a democratically elected government.

However, the Soviet Union blocked the elections in its section and instead, supported Kim Il Sung as leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

In the South, the United States supported SingMan Rhee as the elected leader of the newly founded Republic of Korea (ROK). Both Kim and Rhee were nationalists dedicated to the idea of reunification, although each ruled with a different ideological vision.

In 1949, under a UN agreement, both the Soviet Union and the United States withdrew their military forces from Korea, but both left large numbers of advisors on the peninsula.

The two sides were to continue negotiations over elections to reunify the country, and although the United States preferred that the resulting government not be communist, in 1949 it was still not prepared to commit militarily to preventing that outcome.

Both sides periodically instigated skirmishes across the 38th parallel, but the war formally began when the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, also known as the DPRK crossed the demarcation line and attacked the Republic of Korea the ROK on June 25, 1950.

Both Korean governments had been adamant about reunifying the peninsula, and the Soviet-supported DPRK saw an opportunity to do so with a swift strike.

The DPRK army quickly pushed into South Korea, and by September, it had engulfed almost the entire peninsula and had forced the ROK army into a small area around Pusan.

Upon hearing news of the attack, the United States immediately called for a meeting of the United Nations Security Council, which the Soviet Union was then boycotting over the issue of Chinese representation.

With the Soviets absent, the Security Council was able to pass a resolution condemning the actions of the DPRK and demanding that the Northern armies withdraw from the South.

The United States viewed the attack on the South as evidence that communism would actively challenge the free world and revised its security perimeter to include maintaining a non-communist South Korea. The UN sent forces composed of troops from 15 nations to the peninsula to stop the communist advance.

In September of 1950, UN forces led by U.S. General Douglas A. MacArthur managed to regain lost ground in South Korea and push north, forcing a reaction from the Chinese.

After landing at Incheon, near Seoul, MacArthur’s troops quickly moved to cut off the advancing DPRK army from its North Korean supply lines. By the end of the month, UN forces were approaching the 38th parallel, had liberated Seoul, and had restored the status quo that existed before the war.

The new question was whether to take this newfound success a step further and attempt to liberate the North from the rule of the DPRK.

The leadership of the U.S. and UN forces believed that an attempt to “rollback” the communist forces and unite the country under non-communist rule was well within the parameters of the mission. Chinese leaders had warned the international community that they would intervene in the conflict if UN forces pushed north of the 38th parallel, but MacArthur and other members of the UN command did not believe that either the People's Republic of China or the Soviet Union would attempt to halt UN forces.

With authorization from Washington, UN forces pressed north, and by October 1950 had nearly reached the Yalu River, which marks the border between China and North Korea.

Chinese officials viewed the UN forces approaching the Chinese border as a genuine threat to its security, and late in 1950 they sent Chinese forces into North Korea.

The U.S. and UN had also grossly underestimated the size, strength, and determination of the Chinese forces. As a result, MacArthur’s troops were quickly forced to retreat behind the 38th parallel.

In early 1951, the territory around Seoul and central Korea changed hands several times as the UN and Communist forces advanced and retreated.

MacArthur insisted on the extension of the conflict into China, and on April 11, 1951, he was removed from his command on the charge of insubordination and replaced by General Matthew Ridgeway.

By July 1951, the conflict had reached a stalemate, with the two sides fighting limited engagements, but with neither side in a position to force the other’s surrender.

Both the United States and China had, at this point, achieved the short-term goal of maintaining the demarcation line at the 38th parallel, while the North and South Koreans had failed in the larger goal of uniting the country under their preferred political systems.

Representatives of all the parties began to discuss peace.

On July 27, 1953, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, the Peoples republic of china and UN signed an armistice (the Republic of China abstained) agreeing to a new border near the 38th parallel as the demarcation line between North and South Korea. Both sides would maintain and patrol a demilitarized zone (DMZ) surrounding that boundary line.

The Korean War had long-lasting consequences for the entire region. Though it failed to unify the country, the United States achieved its larger goals, including preserving and promoting NATO interests and defending Japan.

The war also resulted in a divided Korea and complicated any possibility for accommodation between the United States and China.

The Korean War served to encourage the U.S. Cold War policies of containment and militarization, setting the stage for the further enlargement of the U.S. defense perimeter in Asia.

These Cold War policies would eventually lead the United States to regional actions that included its attempts at preventing the fall of Vietnam to communism.

Click the image to enlarge

Click the image to enlarge

The Korean War

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953)[29][a][31] was a war between the Republic of Korea (South Korea), supported by the United Nations, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), at one time supported by China and the Soviet Union. It was primarily the result of the political division of Korea by an agreement of the victorious Allies at the conclusion of the Pacific War at the end of World War II. The Korean Peninsula was ruled by the Empire of Japan from 1910 until the end of World War II. Following the surrender of the Empire of Japan in September 1945, American administrators divided the peninsula along the 38th parallel, with U.S. military forces occupying the southern half and Soviet military forces occupying the northern half.[32]

The failure to hold free elections throughout the Korean Peninsula in 1948 deepened the division between the two sides; the North established a communist government, while the South established a right-wing government. The 38th parallel increasingly became a political border between the two Korean states.

Although reunification negotiations continued in the months preceding the war, tension intensified. Cross-border skirmishes and raids at the 38th parallel persisted. The situation escalated into open warfare when North Korean forces invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950.[33] In 1950, the Soviet Union boycotted the United Nations Security Council. In the absence of a veto from the Soviet Union, the United States and other countries passed a Security Council resolution authorizing military intervention in Korea.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953)[29][a][31] was a war between the Republic of Korea (South Korea), supported by the United Nations, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), at one time supported by China and the Soviet Union. It was primarily the result of the political division of Korea by an agreement of the victorious Allies at the conclusion of the Pacific War at the end of World War II. The Korean Peninsula was ruled by the Empire of Japan from 1910 until the end of World War II. Following the surrender of the Empire of Japan in September 1945, American administrators divided the peninsula along the 38th parallel, with U.S. military forces occupying the southern half and Soviet military forces occupying the northern half.[32]

The failure to hold free elections throughout the Korean Peninsula in 1948 deepened the division between the two sides; the North established a communist government, while the South established a right-wing government. The 38th parallel increasingly became a political border between the two Korean states.

Although reunification negotiations continued in the months preceding the war, tension intensified. Cross-border skirmishes and raids at the 38th parallel persisted. The situation escalated into open warfare when North Korean forces invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950.[33] In 1950, the Soviet Union boycotted the United Nations Security Council. In the absence of a veto from the Soviet Union, the United States and other countries passed a Security Council resolution authorizing military intervention in Korea.

|

The U.S. provided 88% of the 341,000 international soldiers which aided South Korean forces, with twenty other countries of the United Nations offering assistance. Suffering severe casualties within the first two months, the defenders were pushed back to the Pusan perimeter. A rapid U.N. counter-offensive then drove the North Koreans past the 38th parallel and almost to the Yalu River, when China entered the war on the side of North Korea.[33]

Chinese intervention forced the Southern-allied forces to retreat behind the 38th parallel. While not directly committing forces to the conflict, the Soviet Union provided material aid to both the North Korean and Chinese armies. The fighting ended on 27 July 1953, when the armistice agreement was signed. The agreement restored the border between the Koreas near the 38th Parallel and created the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a 2.5-mile (4.0 km)-wide fortified buffer zone between the two Korean nations. Minor incidents still continue today. From a military science perspective, the Korean War combined strategies and tactics of World War I and World War II: it began with a mobile campaign of swift infantry attacks followed by air bombing raids, but became a static trench war by July 1951. |