The IWO JIMA Memorial at Soldiers Walk Memorial Park

THE VIDEO BELOW IS THE SHORT VERSION OF THE CONFLICT. WE ARE RENDERING A MORE COMPLETE VIDEO OF THIS CONFLICT WHICH WILL BE UPLOADED SOONSHORT INTRODUCTION VERSION

Rosenthal's photograph promptly became an indelible icon — of that battle, of that war in the Pacific, and of the Marine Corps itself — and has been widely reproduced

|

|

Iwo Jima

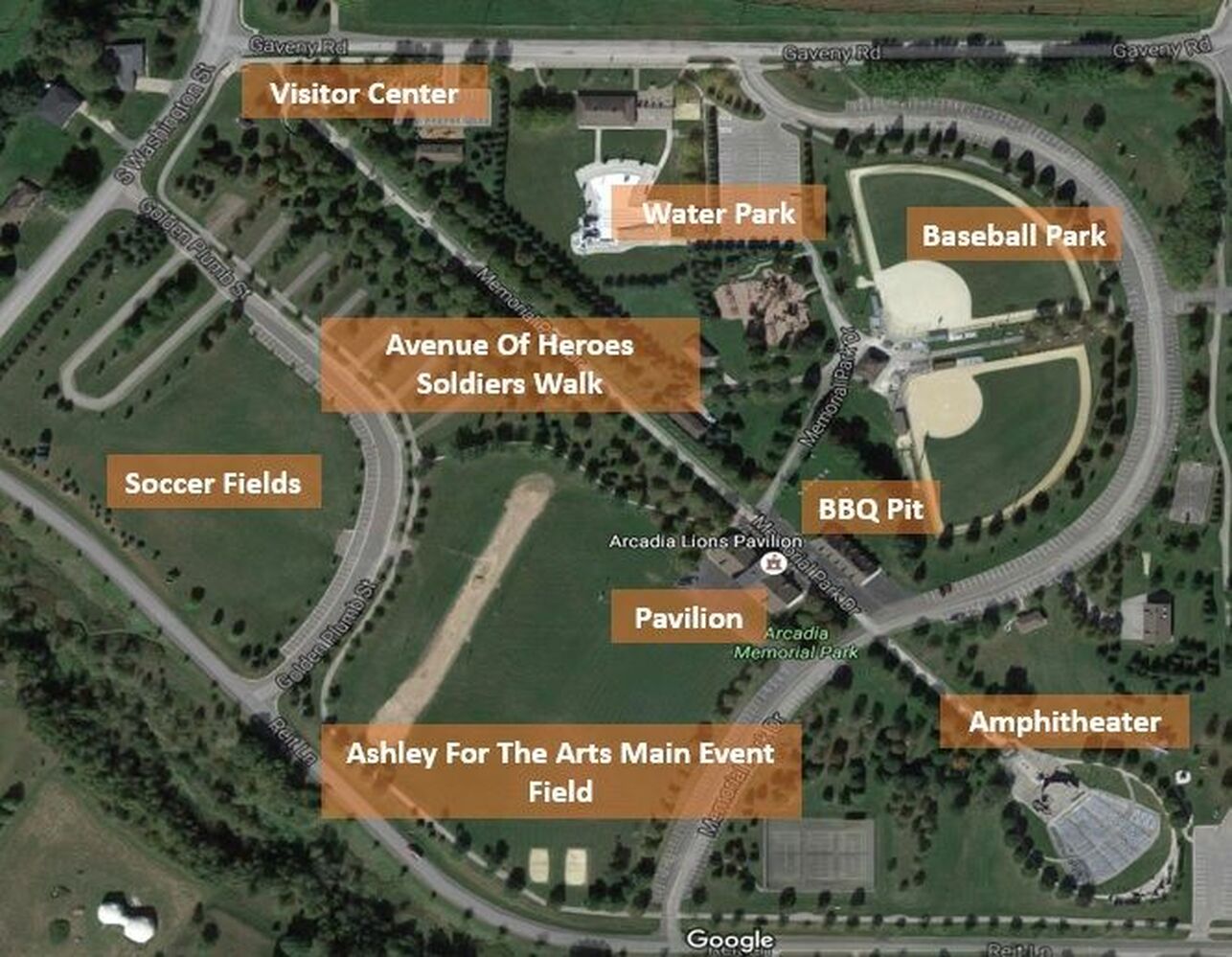

The next memorial you will find on the left is the memorial to the battle of Iwo Jima, replicating a scene that is familiar to everyone, four soldiers erecting the American flag on top of Mt Suribachi. The memorial is 32 ft high, and just a bit smaller than the memorial in Washington D.C. The faces on the statue represent two local boys that fought on Iwo Jima; Russell Severson & Gerald Ziehme. On this memorial you'll find inscribed key moments associated with the battle, World War 2 and more. |

The American amphibious invasion of Iwo Jima, a key island in the Bonin chain roughly 575 miles from the Japanese coast, was sparked by the desire for a place where B-29 bombers damaged over Japan could land without returning all the way to the Marianas, and for a base for escort fighters that would assist in the bombing campaign.

Iwo Jima is a small speck in the Pacific; it is 4.5 miles long and at its broadest point 2.5 miles wide. Iwo is the Japanese word for sulfur, and the island is indeed full of sulfur. Yellow sulfuric mist routinely rises from cracks of earth, and the island distinctly smells like rotten eggs.

Since winning Saipan in the previous year, American bomber commander Curtis LeMay had been planning raids on the Japanese home islands from there, and the first of such bombings took place in Nov 1944. The bombers, however, were threatened by Iwo Jima in two ways. First, the Zero fighters based on Iwo Jima physically threatened the bombers; secondly, Iwo Jima also acted as an early warning station for Japan, giving Tokyo two hours of warning before the American bombers reached their targets. Moreover, the Japanese could (and did) launch aerial operations against Saipan from Iwo Jima.

Finally, the United States could gain an additional airfield for future operations against Japan if Iwo Jima could be captured. In the Philippines, the operation on the island of Leyte was pushed up by eight weeks due to lack of significant resistance, which opened up a window for an additional operation. Thus, Operation Detachment against Iwo Jima was decided.

MORE.....

The defenders under the command of Tadamichi Kuribayashi were ready. The aim of the defense of Iwo Jima was to inflict severe casualties on the Allied forces and discourage invasion of the mainland. Each defender was expected to die in defense of the homeland, taking 10 enemy soldiers in the process. Within Mount Suribachi and underneath the rocks, 750 major defense installations were built to shelter guns, blockhouses, and hospitals. Some of them had steel doors to protect the artillery pieces within, and nearly all them were connected by a total of 13,000 yards of tunnels. On Mount Suribachi alone there were 1,000 cave entrances and pill boxes. Within them, 21,000 men awaited. Rear Admiral Toshinosuke Ichimaru, commander of the Special Naval Landing Forces on Iwo Jima wrote the following poem as he arrived at his underground bunker:

At 2AM on the morning of 19 Feb, battleship guns signaled the commencement of D-Day for Iwo Jima, followed by a bombing of 100 bombers, which was followed by another volley from the naval guns. Little did we know, while the 70 days of aerial bombardment, 3 days of naval bombardment, and the hours of pre-invasion bombardment turned every inch of dirt upside down on this little island, the defenders were not on this island. They were in it. The massive display of fireworks merely made a small dent in the defenders' numbers.

The 30,000 who survived the initial landing faced heavy fire from Mount Suribachi at the southern tip of the island, and fought over inhospitable terrain as they moved forward; the rough volcanic ash which allowed neither secure footing or the digging of a foxhole. The Marines advanced yards at a time, fighting the most violent battles they have yet experienced.

Yard by yard, the American Marines advanced toward the base of Mount Suribachi. Gunfire was ineffective against the Japanese who were well dug-in, but flame throwers and grenades cleared the bunkers. Some of the Americans charged too fast without their knowing. Thinking that enemy strong points had been overtaken, they moved forward, only to find that the Japanese would reoccupy the same pillboxes and machine gun nests from underground exits and fire from them from behind.

Finally, on 23 Feb, the summit was within reach, but the Americans did not know it yet. A 41-man patrol was sent up, Colonel Chandler Johnson gave the lieutenant leading the patrol a flag. "If you get to the top," he said, "put it up." "If" was the word he used. Step by step, the patrol slowly and carefully climbed the mountain, each of them later recalled that they were convinced it was going to be their last, but they made it. Little did they know, they were watched by every pair of eyes on the southern half of the island, and a few of the ships, too.

When they reached the top, Lieutenant Schrier, Platoon Sergeant Ernest Thomas, Sergeant Hansen, Corporal Lindberg, and Louis Charlo put up the flag. Much to their surprises, the island roared in cheers. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, observing from a naval vessel, excitedly claimed that the "raising of that flag on Surabachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years." Equally ecstatic, General Holland Smith agreed with Forrestal that the flag was to be the Navy secretary's souvenir. Colonel Chandler Johnson could not believe Forrestal's unreasonable demand from the hard-fighting Marines who rightfully deserved that flag instead, and decided to secure that flag as quickly as possible. He ordered another patrol to go up to the mountain to retrieve that flag before Forrestal could get his hands on it. "And make it a bigger one", Johnson said.

And so, the second flag went up, and as it turned out, the flag was recovered from a sinking ship at Pearl Harbor. Ira Hayes, Franklin Sousley, John Bradley, Harlon Block, Mike Strank, and Rene Gagnon were proud to have been sent, but they did not think much of it. It was, after all, just a replacement flag. But they did not know that some distance after them was photographer Joe Rosenthal, who was at the place at the right time to take the famous "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" photograph. The photograph was the driving force for a record-breaking bond drive in the United States some time later, and it would also bring Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize.

With the landing area secure, more Marines and heavy equipment came ashore and the invasion proceeded north to capture the airfields and the remainder of the island. With their customary bravery, most Japanese soldiers fought to the death. Of the 21,000 defenders, only 1,083 were taken prisoner, two of whom did not surrender until 1951) the entire garrison was wiped out. American losses included 5,900 dead and 17,400 wounded.

The Allied forces suffered 25,000 casualties, with nearly 7,000 dead. Over 1/4 of the Medals of Honor awarded to marines in World War II were given for conduct in the invasion of Iwo Jima.

In sum, Iwo Jima saw the only major battle in the entire Pacific Campaign where American casualties surpassed the Japanese dead. All the lives lost, on both sides of the battle, for ten square miles; for that very reason, Admiral Richmond Turner was criticized by American press for wasting the lives of his men. However, by war's end, Iwo Jima sure appeared to have saved many Americans, too. 2,400 B-29 landings took place at Iwo Jima, many were under emergency conditions that might otherwise meant a crash at sea.

Battle of Iwo Jima

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Battle of Iwo Jima (19 February – 26 March 1945), or Operation Detachment, was a major battle in which the United States Armed Forces fought for and captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Japanese Empire. The American invasion had the goal of capturing the entire island, including its three airfields (including South Field and Central Field), to provide a staging area for attacks on the Japanese main islands.[2] This five-week battle comprised some of the fiercest and bloodiest fighting of the War in the Pacific of World War II.

After the heavy losses incurred in the battle, the strategic value of the island became controversial. It was useless to the Army as a staging base and useless to the Navy as a fleet base.[4]

The Imperial Japanese Army positions on the island were heavily fortified, with a dense network of bunkers, hidden artillerypositions, and 18 km (11 mi) of underground tunnels.[5][6] The Americans on the ground were supported by extensive naval artilleryand complete air supremacy over Iwo Jima from the beginning of the battle by U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aviators.[7] This invasion was the first American attack on Japanese home territory, and the Japanese soldiers and marines defended their positions tenaciously with no thought of surrender.

Iwo Jima was the only battle by the U.S. Marine Corps in which the overall American casualties (killed and wounded) exceeded those of the Japanese,[8] although Japanese combat deaths were thrice those of the Americans throughout the battle. Of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima at the beginning of the battle, only 216 were taken prisoner, some of whom were captured because they had been knocked unconscious or otherwise disabled.[1] The majority of the remainder were killed in action, although it has been estimated that as many as 3000 continued to resist within the various cave systems for many days afterwards, eventually succumbing to their injuries or surrendering weeks later.[1][9]

Despite the bloody fighting and severe casualties on both sides, the Japanese defeat was assured from the start. Overwhelming American superiority in arms and numbers as well as complete control of air power — coupled with the impossibility of Japanese retreat or reinforcement — permitted no plausible circumstance in which the Americans could have lost the battle.[10]

The battle was immortalized by Joe Rosenthal's photograph of the raising of the U.S. flag on top of the 166 m (545 ft) Mount Suribachi by five U.S. Marines and one U.S. Navy battlefield Hospital Corpsman. The photograph records the second flag-raising on the mountain, both of which took place on the fifth day of the 35-day battle. Rosenthal's photograph promptly became an indelible icon — of that battle, of that war in the Pacific, and of the Marine Corps itself — and has been widely reproduced

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Battle of Iwo Jima (19 February – 26 March 1945), or Operation Detachment, was a major battle in which the United States Armed Forces fought for and captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Japanese Empire. The American invasion had the goal of capturing the entire island, including its three airfields (including South Field and Central Field), to provide a staging area for attacks on the Japanese main islands.[2] This five-week battle comprised some of the fiercest and bloodiest fighting of the War in the Pacific of World War II.

After the heavy losses incurred in the battle, the strategic value of the island became controversial. It was useless to the Army as a staging base and useless to the Navy as a fleet base.[4]

The Imperial Japanese Army positions on the island were heavily fortified, with a dense network of bunkers, hidden artillerypositions, and 18 km (11 mi) of underground tunnels.[5][6] The Americans on the ground were supported by extensive naval artilleryand complete air supremacy over Iwo Jima from the beginning of the battle by U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aviators.[7] This invasion was the first American attack on Japanese home territory, and the Japanese soldiers and marines defended their positions tenaciously with no thought of surrender.

Iwo Jima was the only battle by the U.S. Marine Corps in which the overall American casualties (killed and wounded) exceeded those of the Japanese,[8] although Japanese combat deaths were thrice those of the Americans throughout the battle. Of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima at the beginning of the battle, only 216 were taken prisoner, some of whom were captured because they had been knocked unconscious or otherwise disabled.[1] The majority of the remainder were killed in action, although it has been estimated that as many as 3000 continued to resist within the various cave systems for many days afterwards, eventually succumbing to their injuries or surrendering weeks later.[1][9]

Despite the bloody fighting and severe casualties on both sides, the Japanese defeat was assured from the start. Overwhelming American superiority in arms and numbers as well as complete control of air power — coupled with the impossibility of Japanese retreat or reinforcement — permitted no plausible circumstance in which the Americans could have lost the battle.[10]

The battle was immortalized by Joe Rosenthal's photograph of the raising of the U.S. flag on top of the 166 m (545 ft) Mount Suribachi by five U.S. Marines and one U.S. Navy battlefield Hospital Corpsman. The photograph records the second flag-raising on the mountain, both of which took place on the fifth day of the 35-day battle. Rosenthal's photograph promptly became an indelible icon — of that battle, of that war in the Pacific, and of the Marine Corps itself — and has been widely reproduced